Neighborhood Associations

Help make our city a great place to live

By Fred McKissack

Photos By Neal Bruns

It’s one of the nicest evenings of early summer.

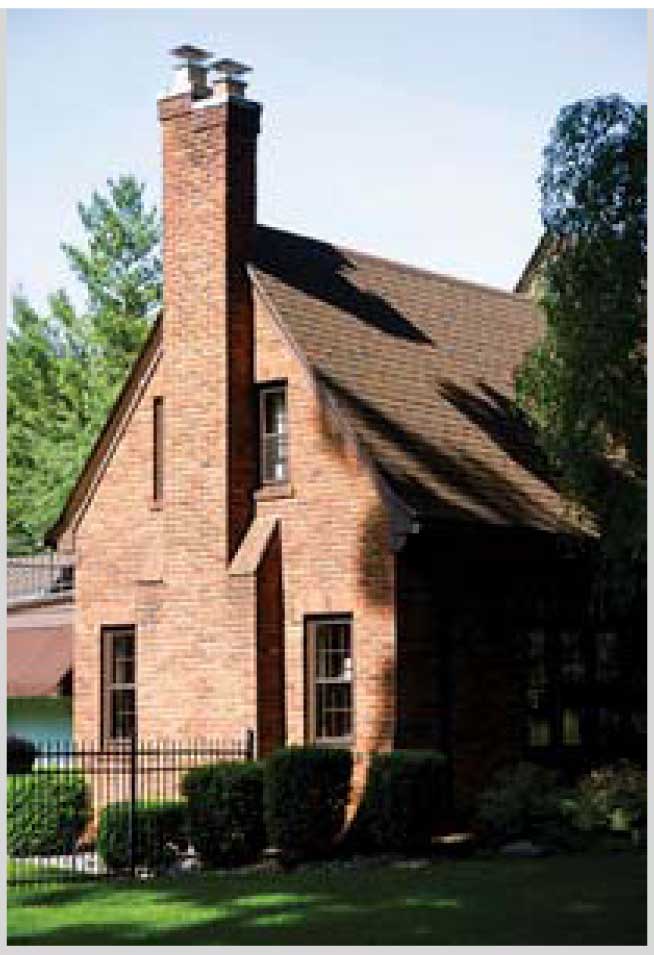

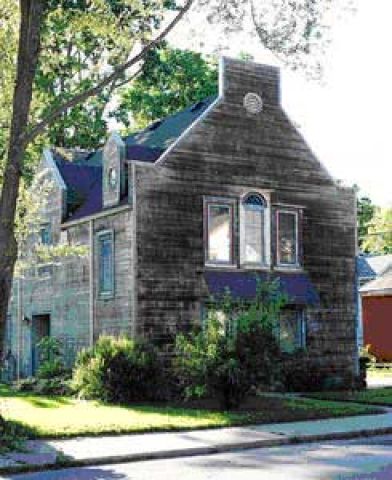

It’s warm in West Central. A setting sun enriches the historic neighborhood’s lush foliage. The eclectic designs of the houses — from the stately colonials to small Craftsman homes — speak to the diversity of the residents. Two tattooed hipster girls saunter down Rockhill Street as a family sits on the grassy side of a wooden duplex after what looks to have been a sizeable cookout. On Jefferson Boulevard, cars pass three kids on well-used BMX bikes who cruise by a well-dressed, middle-aged couple strolling hand in hand past the rear of Grace St. John’s Lutheran Church.

One street north of this typical scene in West Central, four row houses in the 800 block of West Washington are a patch of blight, abandoned for at least a decade. What’s going to happen to them soon is an illustration of the issues facing the modern neighborhood association and the possibilities associations represent. West Central’s association has learned it has ways to address even such serious, expensive problems as these four homes.

In May, the City of Fort Wayne announced it would partner with local Belay Corp. to buy and renovate the structures back to single-family homes. The total cost of the project is $500,000 “less the final sale price of the homes,” which will be priced between $80,000 and $120,000.

In its press release announcing the public-private partnership, the mayor’s office wrote: “… the City coordinated its efforts here with the West Central Neighborhood Association, which has considered this row of homes an ongoing eyesore.”

For Charlotte A. Weybright, a 16-year resident of the neighborhood and its association president, the news about the Belay project is an affirmation of the power of a neighborhood association to improve its neighborhood.

“This is great news for us,” Weybright said. “We’re an older neighborhood in the inner core, so we have issues with abandoned homes and crime … the association is set up to protect the neighborhood. This really is the first level of government participation for the people.”

In the mid-1990s, then-Mayor Paul Helmke’s initiation of community-oriented government elevated the traditional importance of Fort Wayne’s neighborhood associations to new prominence. Neighborhood associations, governed by volunteers and funded by membership dues, always have played an important role in advancing communities. Associations are advocates for public safety and better services, as well as a catalyst for renewal and, sometimes, a roadblock to new development.

In a 2001 interview with The News-Sentinel, Helmke said he found neighborhoods to be the most logical and practical political governing unit through which the city could interact with city government.

Tucked inside her planner, Carolyn Devoe, former Historic South Wayne Neighborhood Association president and current secretary of the Southwest Area Partnership, keeps a city parking garage stub signed by Helmke. It marks the day when the mayor signed a stricter rental-housing ordinance, a series of code violations that could be pressed against landlords and tenants.

“I keep it with me as a reminder of what people can do when they work toward the common good,” she said. “It was a war, but it was worth it to protect the neighborhood and its residents.”

How the neighborhood associations interact with city government constantly evolves. In 2001, Mayor Graham Richards carried on the division of the city into four quadrants, each with an advocate and the area partnership, where associations could coordinate their efforts and exchange information and ideas. Under Mayor Tom Henry, the neighborhood advocates were reclassified as community liaisons and, due to budget cuts, the staff was reduced from four to two: Cherise M. Dixie, working with the southeast and northeast quadrants, and Brent Wake, whose responsibilities are the southwest and northwest.

“The name change better reflects what we do, which is work with the associations, businesses and schools,” said Dixie, who grew up in the southeast quadrant but attended high school at Concordia on the city’s north side. The neighborhood associations, she said, play an important role in Fort Wayne. They add a small-town feel, helping residents get involved at the grassroots. Elected officials generally agree.

“An active association typically has an idea of what they value, what’s important for them, what they’d like to see done,” said councilman Tim Pape, who represents the city’s 5th district, which includes West Central. “(They) are enormously helpful in directing city services and investments.”

It’s a sentiment that is shared by three of his council colleagues, Karen Goldner, who serves the city’s 2nd district, Glynn Hines of the 6th district and Liz Brown, a member at large.

There are 400 neighborhood associations in Fort Wayne. They range in size from Illsley Place, a 38-home association near Foster Park on the city’s south side; to the Arlington Park Community Association, which represents 1,200 homes, has its own golf course, a swimming pool, a triple-digit budget and assets of more than $2 million.

Association dues range from $5 to several hundred dollars in the larger, more recent and upscale subdivisions, where membership is likely to be mandatory and unpaid dues can result in liens or legal action.

West Central is one of the most active associations, a neighborhood that encompasses 470 acres and nearly 1,000 homes on the west edge of downtown, framed by the St. Mary’s River on its north and west and railroad tracks on the south.

Its origins date back to the 1830s. As with many core neighborhoods in the industrial Midwest, the neighborhood changed as the region’s fortunes waned in the 1970s, adding rental properties and absentee landlords and losing commercial and residential buildings to neglect and demolition.

In 1984, according to the association’s history listed in its 2004 plan, a large portion of the neighborhood was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. A smaller area also became a local historic district. The designations sparked a revival. Over the past 25 years, “many rundown homes have been returned to single-family residences,” continues the history in the July 2004 plan. “As a result, property values have risen.”

Essentially, the preservation of property values is the mission of a neighborhood association, for older neighborhoods such as West Central as well as newer subdivisions such as Arlington Park, Countryside Estates and Millstone. If the quality of life is enhanced, if a neighborhood is considered desirable for homebuyers, the value of the homes, even in tough economic times, is protected.

Obviously, maintaining a stable neighborhood goes beyond protecting the aesthetics. Working with the city’s various departments, from code enforcement and police to economic development and public works, is at the forefront of association activities. For example, West Central, Weybright said, has been an influential player in the city’s flood control plan along the St. Mary’s River.

Across town, Tony Ridley, a resident of the southeast since 1960 and president of the Renaissance Pointe Neighborhood Association, has participated in a massive change in his neighborhood. For one, the name: Hanna-Creighton to Renaissance Pointe. Then there is the public-private partnership to redevelop a section of the city that had become a “mini Gary,” Ridley said.

Recently, the YMCA opened a $6 million center at Renaissance Pointe, joining an Allen County Public Library branch, Community Action of Northeast Indiana and the Fort Wayne Urban League in modern quarters along Hanna Street. It’s easy to understand the sense of urgency and hope in Ridley’s voice. Millions were spent on infrastructure upgrades, including sewer and drainage improvements. The credit crunch hurt, but a lease-to-own financing plan sparked interest in potential homebuyers.

Ridley buzzed about a beautification project along South Anthony Boulevard, the sale of Eden Green and the plans to rehab the apartment complex and a $10 million investment in the building of 66 new homes. It’s hoped more “roofs” will lead to more retail and restaurants.

“It’s been a long time coming, and it hasn’t been easy, nor was it the effort of one person,” he said.

Ridley and Heather Presley-Cowen, the city’s deputy director of housing and neighborhood services, pointed to the work and dedication of longtime neighborhood advocates such as Bertha Rogers, Mary Turner and Byram Trice. Presley-Cowen, who likened the neighborhood’s resolve to a phoenix rising, also credited Councilmen Hines and Pape and various faith communities for campaigning for redevelopment.

Illsley Place is a 38-home neighborhood bounded by Broadway to the west and Beaver to the east and bracketed between West Oakdale Avenue and Rudisill Boulevard.

It’s one of the city’s smallest neighborhood associations. Its annual meeting is held on Memorial Day, according to its president, Adrianne Maurer. The meeting comes after the annual parade by the neighborhood children, which is followed by a party at the home of a resident. She’s lobbied the city for services, including working with ash trees.

Save for the odd garage vandalism, crime is negligible, she said.

It sounds like everything is just fine, yet Maurer, who is currently the president of the Southwest Area Partnership, a group that includes some of the tonier neighborhoods in Southwest and Aboite, sees Illsley Place, due to urban density, as an important link with surrounding neighborhoods. No matter how isolated Illsley Place appears on a map or in person, the economic situations in adjacent communities impact Illsley, Maurer said.

The Packard Area Planning Alliance, for example, consists of Oakdale, Fairfield, Creighton-Home, South Wayne, Williams-Woodland and Illsley Place neighborhoods. It’s a 555-acre area and home to more than 7,600 people of varying socio-economic statuses. It’s 80 percent residential. Founded in 2003, the alliance’s vision statement is simple: to cultivate “the livability and visual appeal of the area through improved preservation and maintenance of existing housing stock, increased emphasis on the historic assets of the area, enhanced recreational and cultural amenities, and heightened community spirit throughout the seven-neighborhood area.”

It’s a pro-active approach to bring attention to a section of the city that, Maurer said, “is the best kept secret in Fort Wayne.” She added: “I’m tired of it being a secret.”

Neighborhood associations can also find themselves at the center of zoning disputes when residents find someone’s plan for nearby property impinges on their quality of life. Residents of Millstone Village, a subdivision west of Lima Road in the city’s northwest quadrant, were embroiled in a battle with Crazy Pinz over the development of an outdoor entertainment area on 9.6 acres of land adjacent to the subdivision. After many meetings and neighborhood appearances at Plan Commission and City Council meetings, Council voted the request down 5-4.

Millstone Village Association President Nicole Woods said despite media reports, the relationship with Crazy Pinz wasn’t always contentious. Indeed, the first page of the association’s fall-winter 2006 newsletter heralded the opening of Crazy Pinz, including the business’s logo and a picture of construction, along with information about a “free day” for local residents for a dry-run opening of the facility. Things have changed. Neighbors have complained to police about noise and vandalism. Council member at-large Marty Bender, a deputy chief of police, told The News-Sentinel he pulled pages of reports detailing police activity at the bowling alley.

Woods said the association’s intent wasn’t to close Crazy Pinz. However, she added, its owners’ wish to rezone would have had a negative effect on the residents. Unfortunately, there could be no compromise.

“No one wants to hear music blaring at 9 p.m. when they’re trying to get their children to sleep,” said Woods, who moved to the neighborhood in 2004. “I’m not sure if this is a success yet,” she cautioned. “This could be a never-ending cycle.”

Goldner, one of the four council members who voted in favor of Crazy Pinz, struck a conciliatory tone when asked about this episode.

“In a democratic system of government, we need to have all interests heard and considered,” she said. “That is not always an easy balance to achieve, but it is better than not having those interests represented.”

One of the more contentious issues involving neighborhood associations is restrictive covenants. Proponents view them as necessary to the common good to preserve both way-of-life and property value. Opponents see the covenants as anathema to the rights of a property owner.

Covenants aren’t a matter of older city neighborhoods contrasting with newer suburban developments, because only the absolutely oldest neighborhoods were developed without covenants. You can look at current covenants online through the county’s recorder’s award-winning neighborhood resource center at www.allencountyrecorder.us.

In Southwood Park, developed in the early 20th century on the city’s south side, residents recently voted to update several items in its restrictive covenant. They eliminated racist language from the covenants dating back to its original platting and enacted rules against splitting single-family homes into duplexes and, with some caveats, renting out single-family homes.

Illsley Place didn’t follow its neighboring association in banning turning homes into rental property. Indeed, Maurer said there are two families in rental homes in the neighborhood, and she finds it effective to include them in the discussion of the association’s decisions.

On the other hand, Millstone Village, a relatively young community in the city’s northwest, has 14 pages of limitations dated to 1992, including the length and width of driveways, dumping, animals (no livestock or poultry) and even oil drilling. There is a separate document for architectural guidelines on the association’s website.

Things that violate a neighborhood’s covenants don’t always violate city code, but sometimes the Neighborhood Code Enforcement department gets involved. Usually, involving code enforcement will help, Millstone’s Nicole Woods said. But there are times when a homeowner’s disobedience of a restrictive covenant requires a stern letter from the association’s attorney.

In West Central, much of which is subject to building restrictions linked to historic preservation, Weybright said she’s gotten calls from residents who wonder why they’re unable to do whatever they want to the exterior of their home.

“Some people are surprised that you just can’t yank out windows, pull down doors or put up aluminum siding,” she said.

County Recorder John McGauley’s advice for home buyers and current home owners is simple: If you intend to buy, check the covenants to see what you can and cannot do; if you’re already a homeowner, check the restrictive covenants before you decide to erect a shed in the backyard or start a home business.McGauley’s office is where liens are filed against homeowners not paying mandatory association dues. Last year, for example, Arlington Park filed liens against 50 homeowners for failure to pay association dues as listed in the neighborhood’s covenants. Not all neighborhoods have the authority or feel compelled to be as aggressive. Countryside Estates is a 130-home neighborhood on the city’s northeast side that was annexed to the city in the mid-1990s. It has problems getting residents to pay $35 yearly dues, money that goes for snow removal and landscaping. The economic downturn has hurt, said Shawn Smith, association president. Attorney fees and court costs are too much to go after scofflaws, he added. Homeowner apathy is a perennial problem across neighborhood associations, regardless of the quadrant. When there’s a problem, people come forward, but it’s hard to sustain involvement when things are quiet. Ten percent of the city’s neighborhood associations are listed as inactive. Even in active communities, board seats go unfilled and homeowner participation at monthly meetings is low.

“People have lots to say, but when it comes time to do something, well …” Smith sighs.